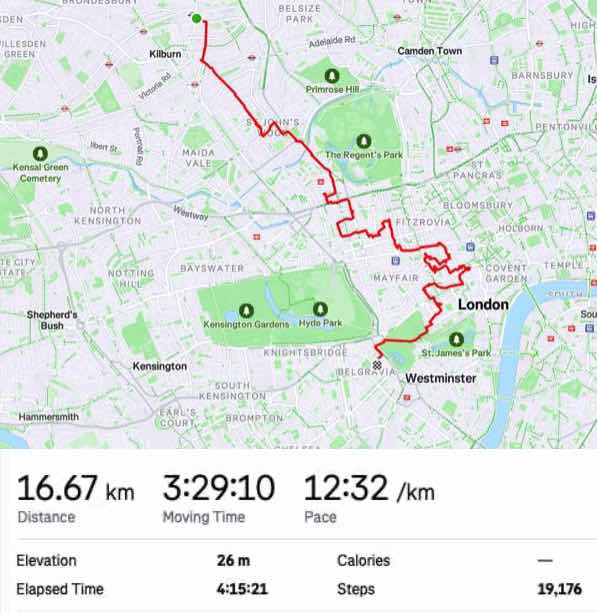

A Beatles-themed walk through the streets of London (March 2025).

Decca Studios

I get the Underground to West Hampstead, exit the station and turn right. I am feeling dodgy from the previous night’s beers, I think I’ve worked out that three is my comfortable limit and anything beyond that is playing with fire.

Perhaps I should switch to wine.

I buy a hot pastry from a local bakery and carry on up West End Lane. I want a bench to sit down and eat and check the map, the road I had expected to cross isn’t appearing and I am starting to think my memory of the route must not be 100% perfect1.

I stop, bite into my chicken bake, squirt boiling hot gravy over my fingers, and check my map – I had gone the wrong way.

I had also forgotten to put Strava on, so make my way back to the station, chomping messily on my breakfast as I dodge down the busy pavement – cross the road until I realise I am now on the wrong side, so cross back. I activate Strava as I pass the Tube entrance, thus making it look like I’d been correct all along, and soon find my starting point: Decca Studios at 165 Broadhurst Gardens.

There’s a blue plaque there now, but it’s for Lonnie Donegan – The King of Skiffle – not The Beatles. A nice touch of irony as it was Donegan’s skiffle craze that first inspired The Beatles to try their hand at music.

The Beatles, at the time still with Pete Best on drums, had driven down from Liverpool on New Year’s Eve, a lengthy ten-hour drive in the days before motorways, and maybe that’s partly why a croaky and nervous band turned in a flat audition. They exuded none of their charisma as they – on Brian Epstein’s advice – plodded through a few mediocre cover versions and some weak examples of what Lennon and McCartney were capable of as songwriters.

Little wonder they failed, and one can hardly blame Decca for saying no to these unknown scruffs from the sticks2. They were never great musicians anyway, their thing was their charm and energy, their sublime vocals, and their brilliant songwriting – none of that was on display at that first audition on New Year’s Day in 1962.

This is my starting point today because it was also the starting point for the The Beatles in London. It would be June before they made it to Abbey Road for an audition at EMI’s Parlophone Records, but – according to Google – it’s only going to take me 29 minutes to walk the 1.3 miles between the two studios.

(I decided to include videos to bring my posts a bit more to life, though they might have been better in landscape orientation).

Abbey Road Studios

The walk from West Hampstead takes me down the charming Priory Lane, a posh avenue lined with lovely big old houses. I wonder had The Beatles signed with Decca how different things might have been.

Would Pete Best have been fired?

How different would they have sounded without George Martin producing them?

Would they have been given the same creative freedom and made the same movies (I could live without the movie Help!)?

Would they even have succeeded as they did, or would they have been like The Tremeloes, the band Decca chose to sign instead, which is the most anyone really expected anyway (including The Beatles themselves)?

Would Paul McCartney have bought a house on Priory Lane instead of Cavendish Avenue?

I get to the junction where Priory Lane meets Abbey Road and turn right. I check my map just to be sure, and Google tells me I should have turned left. I zoom out, not quite trusting that I hadn’t accidentally put in the wrong destination … surely it was to the right? … My sense of direction rarely errs, but it turns out Google is right and my legendary sense of direction is, not to put too fine a point on it, not entirely perfect, and not for the first time today.

Abbey Road is longer than I expect, and much less nice than Priory Lane, but it gets nicer as we near the studios.

The crowds outside Abbey Road Studios are visible from quite far down the road, and I feel a little flicker of smugness because I am not just a tourist skimming the surface by visiting the most-obvious location, I’m a serious Beatles fanboy spending an entire day visiting obvious (and not-so-obvious) locations … that’s entirely different.

The shop is crowded. I read the timeline inscriptions on the wall on the way in, a detail most people whizz by, seemingly uninterested in that extra layer of musical history … my flicker of smugness grows into a flame … I whizz around the shop, uninterested in the tat on offer, and go back to the street outside to take a couple of photos of the famous studio facade.

It was known simply as EMI Studios back when The Beatles were recording here, it only changed its name to Abbey Road Studios in 1976 to help EMI make even more of their link to the band – an example of just how much power shifted from record companies to artists over this period, although it would take many more decades (and technological advances) for the balance to fully shift

Originally pop music was a commodity curated by businessmen who made bags of money from grateful stars who shone for a couple of years, then faded into the cabaret circuit as the money-men moved on to the next big thing. The Beatles broke every bit of that mould, not just becoming their own bosses (the power shifting from capital to labour maybe?), but also being one of the first to sustain their success over many years.

The music business had been shifting ever since recorded music had become a thing – before that it was live performance only (later also via a wireless) – meaning not only could more people hear music (and hear it repeatedly), but also performers could become stars in their own right. This meant audiences latched on to individual performers, and so individuality in performance became important – and if performers can be themselves rather than faithfully (and, to some extent, anonymously) reproduce the works of great composers, we get innovation, improvisation and personality … we get jazz, and greats like Louis Armstrong opening the door for so many other performers to flourish.

I’m skipping over things a bit here, many innovative stars like Ray Charles, Buddy Holly and rock’n’rollers like Little Richard form part of the story, but so as not to make this post entirely about the history of pop music, let’s jump to Elvis Presley and our old friend Lonnie Donegan who were probably the two biggest influences that helped prepare the ground for The Beatles: Elvis was the first to be a proper performer, with film-star looks and sexy moves, he was maybe the first whose performance and image outshone his music, with fans buying into the concept of Elvis as much as his songs. Elvis created Elvis-mania, and although not the first to blast away the cobwebs of stuffiness in the pop world, he certainly made it acceptable for a more informal approach to dance and performance, and a more emotional sexual audience response; Lonnie Donegan, in contrast, was nothing like Elvis, but he democratised music, by showing that non-virtuoso musicians could pick up a guitar or a washboard and thrash out some tunes – before then, it was a high-end craft, with even pop played by accomplished industry musicians, Donegan proved that – as Radiohead would later sing – anyone can play guitar.

Anyone can … but no one was going to pay them to do so unless they got a record contract, and so after the failure of the Decca audition, a determined Brian Epstein, using all his contacts as a successful record-store owner, eventually got The Beatles a try out with Parlophone, a small side-label EMI had picked up in Germany, focused mainly on spoken-work recordings such as The Goons. Rumour had it that EMI were thinking of closing it down, and so its boss – George Martin – was open to taking a few risks, and although he had doubts about their musicianship, he was charmed by their cheeky chutzpah, and decided to give them a go … as long as he could use a session drummer for recordings as he was particularly unimpressed with Pete Best’s noisy basic drumming – the band decided instead to fire Best and replace him their friend Ringo Starr from Rory Storm and the Hurricanes and it went quite well from that point on – so much so that almost 63 years after that audition, there’s a gift shop and a crowd of people outside the studio.

Predictably the zebra crossing is full as people take photos – I don’t blame them, I’d do the same if I were not alone – I cross, hurrying to show I’m not just another tourist – and then head south, on to my next destination.

Paul McCartney’s house

I don’t want to linger at 7 Cavendish Avenue, the lovely house Paul McCartney bought, just a few minutes walk from the studio. He was a much more sensible chap than the other Beatles, picking a private and secure property, right in the heart of both his professional and social lives. The others all bought large suburban properties in the stockbroker belt, with Lennon in particular regretting not being more connected to the big city.

I walk down Abbey Road, turn left along Circus Road and then hang a right into Cavendish Avenue. McCartney’s house is about halfway down on the right. I take a quick snap, but move on, it’s a private home and just because someone’s famous doesn’t mean we don’t have to be respectful and polite.

In the sixties there would have been gaggles of fans hanging around here, and I feel a little envious that they got to live through this and I didn’t. I don’t know how much the band intended to become so much more than just pop stars, I suspect it crept up on them, bit by bit: first they get a hit record, then their shows sell out, and suddenly they’re on the radio and TV, they’re household names and the girls are screaming, but they’re still just making slushy British-y rock’n’roll pop at top speed, still expecting all the success to come crashing down any moment … quick, make a movie … cash in while you can … and so we get to our next stop where the opening scenes of A Hard Day’s Night were made: Marylebone Station.

It is a 25-minute walk on Park Road, running alongside the edge of Regent’s Park. I wonder where I’d have lived had I been a Beatle, I like to think I’d have been as smart as Paul and stayed in this area, and not just followed the others to the burbs – in real life, I grew up in the leafy suburbs, and as a reaction to that have always hankered after an urban lifestyle, but had I grown up in gritty urban post-war Liverpool, perhaps the gentle verdant hills of London’s stockbroker belt would have looked a lot lovelier.

Marylebone Station

This bit of the walk isn’t that interesting, and as I’m weary from not having slept well the night before (which is because I drank too much beer, I know), I’m not really enjoying this stretch. The last two stops had a gravitas to them, they are physical spaces closely associated with something I love. I wanted to be in those same spaces, even if the events are way in the past, and now, having moved on, there’s a bit of an anti-climax. They’re just spaces, a studio and a house, nothing much happening, the emptiness making it clear I’m six decades too late.

I like Marylebone Station.

It’s kind of an eccentric folly now, with only the Chiltern Line (with branches to Oxford, Stratford and Birmingham) and the remnants of the old Great Central Main Line (now only going as far as Aylesbury) docking in to this, the newest and one of the smallest of London’s terminus stations … but therein lies its charm. Yes, it connects to Birmingham, but not the main New Street Station like everyone else, instead it uses the tiny Snow Hill just up the road – typical Marylebone, it can’t just conform and join up in a normal way, it has to do its own little thing, running alongside the rest of the world, adjacent rather than connected, quietly dancing to its own little tune.

I linger a little in the street, looking for angles I remember from the film – if you haven’t seen A Hard Days Night, or if you can’t remember it, this stop is going to mean very little beyond looking at a nice station, so it’s worth doing your homework first.

This is also where George met Patti Boyd.

She was a young actress working as an extra in the film3, and George was besotted with her. According to Peter Brown in his excellent book The Love You Make: The Inside Story of The Beatles, George was a right pain in his pursuit of her, and similarly painful in his crowing about how much his new girlfriend looked like Brigitte Bardot for an annoyingly long time after – it’s easy to forget how young The Beatles were at the time

Marylebone Registry Office

Google tries to send me back the way I came to get to the next stop, but I’m not having that, I don’t go back on myself, I move forward … so I nip down the deceptively-named Great Central Street, which is not very Great and not very Central, at least not in reference to the rest of London, and turn left along the busy Marylebone Road heading for the Town Hall. This is where, in 1969, Paul married Linda Eastman – the American photographer who has nothing to do with the Kodak-Eastman photography company, despite the name. Her father was actually a lawyer and he was Paul’s choice to take over the Beatles management when Brian Epstein died – the other Beatles didn’t like this idea, thinking (with some justification) that it would put Paul even more in the driving seat of the band, and they preferred Allan Klein, then manager of The Rolling Stones. No one thing caused The Beatles to split up, but this (along with John’s heroin addiction) was arguably the single biggest factor, and the legal wrangles that followed are the main reason Paul was estranged from the rest of the band – especially John – for years after.

This location was also where, in 1981, Ringo married Barbara Bach, and in 2011, Paul married his third wife Nancy Shevell – this shows just how much Marylebone was The Beatles’s ‘hood, the part of London they felt most connected to, as the next few stops in this walk illustrate.

Apple Shop

Apple Corps was the company the band formed to be the holding company for all their business activity – the problem wasn’t creating a company to reduce tax exposure, it was the ridiculous concept of the company they chose to create. This was the Swinging Sixties, Sergeant Pepper had shaken the world, and The Beatles were the unassailable face, sound and sight of this avant-garde creative explosion. They were world-famous mega-stars with sky-high confidence, widely heralded as geniuses, and so surely they could turn their hands to anything? … well, no, as Magical Mystery Tour had shown that just because you’re good at music, doesn’t mean you’re good at films, Apple Corps would go on to show that just because you’re good at music, doesn’t mean you’re good at business.

The idea was that rather than give 96% of their money to the taxman (the lyrics to George’s brilliant song make the marginal rate clear: “one for you, nineteen for me“) they decided to become a cash-dispenser for anyone with an artistic idea, however crackpot or unworkable. Part of the plan was to open up The Apple Boutique at 94 Baker Street (according to Paul it would be “a beautiful place where beautiful people can buy beautiful things”) instead it became a beautiful place where normal people, beautiful or otherwise, could steal beautiful things, and so vast amounts of money would be lost.

It’s only minutes round the corner from Marylebone Town Hall, but that short walk separates us from one of Paul’s best ever decisions (marrying Linda) to one of his worst (the Apple Boutique) – not that it was all Paul’s idea by any means, but he was the driving force and level head of the band by this point. At least there’s a blue plaque on the building, so there is that solace, though oddly it describes this corner spot as being where John and George worked (Apple’s offices were initially on the floors above the store, so perhaps the plaque is for that). I assume Paul and Ringo are missed off because they are still alive4 – lucky escape!

Montagu Square

It’s sad that so many people took advantage of their idealism and naïvety, but if your business model is to give money away, it’s inevitable that that will happen. A different kind of sad Beatles thing was the way John treated Cynthia. Their marriage was never a meeting of souls, and John grew increasingly bored and frustrated, and hated feeling tied down and disconnected from the excitement of London – he was young, rich and famous, he didn’t want the pipe and slippers thing, and when Yoko captured his imagination with her avant-garde quirky art and brazen confidence, Cynthia was pretty much out the picture. Initially she and their son Julian moved to Ringo’s flat at 34 Montagu Square in Marylebone, while John and Yoko stayed out in Kenwood in Weybridge, but this made no sense and they swapped over – and so this is where he and Yoko lived, and were later arrested for possession of marijuana (luckily they’d tidied up all the heroin!).

The walk from Baker Street is short, and not much happens, and it’s easy to find the right place due to the blue plaque stuck on the wall. It seems odd that people are working on the property, as if real people just live there, willy-nilly, it’s remarkable history almost erased – didn’t Jimi Hendrix live here too? – it feels wrong to be just living here and changing things like nothing happened.

Manchester Square

EMI’s offices at 20 Manchester Square have been literally erased – the building, including the famous staircase the band used for the cover of Please Please Me (and later the blue and red compilation albums), are all gone – maybe this isn’t even worth a stop to anyone but the most ardent fan because there is nothing to see except the rather nice building erected on the site of EMI’s offices … what a pity they didn’t find a way to keep the stairs for tourists to take photos … oh well, on to Wimpole Street …

Wimpole Street

Paul’s girlfriend Jane Asher lived with her family at 57 Wimpole Street, and when the band decided to fully relocate to London, Paul moved in to the room at the top.

The walk from Baker Street to Montagu Square to Manchester Square and on to Wimpole Street is short, each site being within a few hundred metres of the previous one – the longest leg is the bit to get to Wimpole Street, which crosses back over Baker Street and through the lovely little streets of Marylebone village, another area I didn’t know at all – one definitely worth coming back to.

The tall town house looks like it’s been converted into flats, and there are normal people living here too, possibly unknowingly occupying the very room Paul used to write Yesterday. There’s no blue plaque here because Paul is still alive, as are Jane Asher and her brother Peter (who was one half of singing duo Peter and Gordon), so I guess this is going to be chock full of blue plaques one day.

It’s fun to imagine the clusters of fans who must have camped out here, desperate to catch a glimpse of their hero, and how Paul would evade them by sneaking out the window round the back of the house to make his covert egress via the obliging neighours.

London Palladium … and a detour

I cut down through the last few streets of Marylebone and emerge on to the garish busyness of Oxford Street, one of my least favourite bits of London. Instead of heading straight to the Palladium, I decide to detour to Bedford Street and see if Sister Ray Records has a Beatles CD I could buy to add to my collection – it doesn’t, I’ve got most of them, but am missing some of the early albums so had hoped to pick up a copy of one as part of the walk. I go on to Reckless Records over the street, I like this shop less, it’s less friendly and has less stock, but I think my ask is pretty straightforward: any of the Fab Four’s first four albums on CD … but no, not here either.

My switch back to CDs is fairly recent. As someone born in the seventies, who cut his musical teeth in the eighties then enjoyed the nineties (perhaps a little too much at times) I had gone from being an avid vinyl collector to an avid CD collector, having a substantial collection of both (though both have been severely thinned out over the years). As downloads then streaming took over, I became much more discerning, only buying favourites or special editions that had meaning, initially vinyl because it’s a more beautiful object, but then I realised CDs were a third of the price and much easier to play, and so this opened up a lot more opportunities than persevering with overpriced vinyl records. Putting a CD on still gives me a high-quality musical experience that helps me fully engage with the album in a way that streaming doesn’t, so – until I change my mind again – I’m quite happy with my decision.

I need a sit down and so go to Leon for lunch, a fast-food place I’ve come to appreciate on my trips back to London – the concept of serving food that’s actually good for you and responsibly and locally sourced shouldn’t be the exception, but oddly it is.

I finish, check my messages, and walk on to the London Palladium on Argyll Street where, on 13th October 1963, The Beatles topped the bill at the Sunday Night at the London Palladium TV show – another Brian Epstein masterstroke. The band had had a couple of hits and Beatlemania was kicking in, but the London press were mostly ignoring them because they were northerners, and prejudice in England against its northern provinces was a real thing back then (and remains so today, although less so). The gig is a success, they win over the crowd inside and the crowd outside wins over the press who decide that, despite them being from Liverpool, they might be something worth writing about.

I arrived at the Palladium via the top end of Carnaby Street – I had heard there was a statue of John Lennon here called Imagine, and the only statue I can find is this one of a man on a bench that doesn’t look much like Lennon to me, but I’ll put it here anyway, because I checked on Wikipedia and yes, it is him.

I duck back down Kingly Street where the Bag o’ Nails club used to be (number 9, Kingly Street), the club where Paul met Linda and first saw Jimi Hendrix (also rumoured to be where Fleetwood Mac’s John McVie met Christine Perfect (who would become Christine McVie)) – it was one of the main rock’n’roll hangouts back in the day, but now seems to be something called The Little Violet Door as far as I can tell.

Millings and Drum City

I walk through Soho to 63 Old Compton Street which used to be a tailor called Millings. It was the place the band got their suits. I knew it wasn’t a tailor any more, but thought it was a Spanish café, but I couldn’t even find that, despite walking up and down the street a couple of times. The only thing that seemed to be occupying the site was an Italian restaurant called La Pastaia. Oh well, including this in the list feels like a bit of a stretch anyway, especially as it’s no longer a tailor, so I shrug my weary shoulders and head to a similarly disappointing Drum City (112A Shaftesbury Avenue) where, in April 1963, Ringo got his drum set and they designed that famous Beatles logo – now it’s a rather nice bookshop called Guanghwa.

Prince of Wales Theatre

Heading back along Shaftesbury Avenue, then left down Rupert Street we get to the Prince of Wales Theatre, where, on November 4 1963, The Beatles did the Royal Variety Show and John Lennon famously said:

For our last number I’d like to ask your help. Would the people in the cheaper seats clap your hands. And the rest of you, if you’ll just rattle your jewellery.

The Beatles were not just another bunch of polite grateful pretty boys, they were cheeky and irreverent and funny, perhaps their collective band personality was mostly an extension of Lennon’s back then – certainly John was the band’s clear leader at this point – and it was moments like this that made them stand out. The mould for rock stars from this day forth was that of non-conformist, of a sneering disregard for convention and their elders – would bands like The Rolling Stones or The Who have been so openly rebellious without Lennon showing them they didn’t need to follow the old rules?

Apple Corps

I walk along Coventry Street, through Piccadilly Circus, up Regent Street and left down Vigo Street. A little way down, before it becomes Burlington Gardens, Savile Row branches off to the right, and at number 3 are the old offices of Apple Corps where the band played their last performance on the rooftop. If you’ve seen footage of that concert, or watched the excellent Get Back films, you’ll know this spot well.

This is a biggie and I loiter a little. After the mundane stops of tailors that aren’t tailors, or theatres that are just theatres, this one feels important. This is not quite Abbey Road level of Beatlesy-ness, but it’s pretty damn close – and not that I’m getting my knickers in a twist about this whole blue plaque malarkey, but if you can mount a Beatles plaque here, you can put a proper one on the old Apple Store on Baker Street.

Indica Books and Gallery

I walk through Burlington Arcade, cross Piccadilly and head down Duke Street. I briefly pop into The Chequers Tavern for biological reasons, before realising I can use the pub to get into Masons Yard if I head out the back way. It was here in 1965 that some of Paul’s friends opened Indica Books and Gallery (at 6 Masons Yard), an avant-garde “alternative” space that, amongst other things, led to a show by Yoko Ono that John attended – hence Yoko gets her own mural at the other end of the yard.

John had never felt comfortable being a pop star, he was frustrated by feeling like he was selling out – his cry for Help! was meant literally – and, heavily influenced by Bob Dylan, was trying to become a more artistic and intellectual figure. He’d already had books published, and was increasingly interested in different kinds of art, and was fascinated – and probably bewildered – by Yoko’s exhibition – including a step ladder that led up to the word “Yes” in tiny letters on the ceiling (hence the mural). It was here that they first met, although it would be a while before they properly got together.

Brian Epstein’s house and the local pub

I walk out of Masons Yard, down Duke Street St James’s, turn right along King Street, cut across St James’s Street and find my way out into Green Park via Stable Yard. I glance at Lancaster House, and the more modest Clarence House I can just see the corner of – this, rather than Buckingham Palace, is where King Charles actually lives.

Green Park is probably the least lovely of London’s central parks, but it is still nice and on this sunny day is bustling with life. I walk up, glance across at Buckingham Palace – you could, at a stretch, include the palace as a Beatles location because it was here they famously got their MBEs, but I think that’s even more of a crowbar than including a pasta restaurant that used to be a café that used to be a tailors.

I walk up the edge of the park, parallel to Constitution Hill, across the edge of Hyde Park Corner and down Grosvenor Place – Brian Epstein chose not to live in Marylebone, or St John’s Wood, or out in the Weybridge sticks, he chose this super-posh corner of Belgravia. Where we choose to live says a lot about us, especially if – like Epstein and The Beatles – we have financial capacity to live wherever we want.

What did this choice say about Brian? Was he looking for establishment approval? For acceptance into the upper layers of British society?

Number 24 Chapel Street looks nice, it occupies a good corner spot on this quiet central street, I can see the attraction, although the quiet grandeur is not really my thing, I reckon I’d have been more of a Marylebone man had I been in the band5.

Heading down Groom Place I get to the tiny little pub that The Beatles would sneak off to – the pub was not well-known, and the band could nip out of Brian’s house and get some privacy, being treated like normal people for a short time before being shoved back into the exhausting hurly-burly of Beatlemania and the constant demand for tours and new music – a couple of pints in this lovely little local must have felt like heaven.

This is the end of my tour, and I don’t buy anything at the pub. I don’t want anything really, I just want to get back to my hotel, get my bag, and sit down with a cup of tea and nurse my hangover until it’s time to leave for King’s Cross and my train up to Leeds.

Footnotes

- Another word for my memory of the route would be “wrong”. ↩︎

- Decca learnt from their mistake, and were quick to sign The Rolling Stones, offering them one of the best royalty deals for a newly signed band ever. ↩︎

- She’s one of the schoolgirls in the rail carriage that John Lennon goads in his annoyingly goofy way. ↩︎

- This was a correct assumption, according to English Heritage: “To be awarded an official English Heritage plaque, the proposed recipient must have died at least 20 years ago.” – this is, they argue, “to help ensure that the decision … is made with a sufficient degree of hindsight” – sensible, but arguably the passage of almost 60 years since The Beatles were active in London is enough time without them all having to die. ↩︎

- Given the choice, I’d have been George. I am not a purist, I love The Beatles but am not someone who things cannot be changed or improved, and to my mind, George was the most replaceable. John and Paul obviously not, and Ringo was too important as a personality as much as a musician, his easy-going lovable humour was the glue of the band, but George … a more touchy and awkward figure, and not a great guitarist – perhaps I could sneak back in time, learn the guitar and usurp his spot?! ↩︎